Whispering from the Sky is a twelve-channel sound installation made for the Robinson Library in Armagh (Northern Ireland) - a beautiful 18th century building constructed for the then Archbishop of Armagh, Archbishop Robinson, which was the earliest public library in Ulster, and still houses the majority of books and artefacts from that original collection. In 1770 a census was taken by William Lodge at Robinson’s behest of all those living in Armagh, detailing where people lived, how many were in each household, what they did for a living, their religious affiliation and in some cases their economic status. In 2019 - some 250 years after the information was gathered for that census - this project sought to involve the current inhabitants of Armagh in that history. It features the spoken voices of current residents reflecting on the contents of the survey, the manuscript of which is still kept in the library.

The installation’s initial manifestation, during the Armagh Georgian Festival in November 2019, formed part of a larger project - Splendid, Liberal, Lofty - with visual artist Helen Sharp and poet Maria McManus, who also took their inspiration from objects in the Robinson Library, and from their interactions with the people of Armagh.

There is necessarily something paradoxical about animating the silent space of a library with voices. Libraries, especially historic academic libraries, are spaces of quiet contemplation, but the 29 pages of the Reverend William Lodge’s small leather-bound notebook are bursting with pencilled life, ending with a summary noting that the population of 1,910 inhabitants was made up of 502 families, 162 of which belonged to the Church of Ireland, 131 were Presbyterian, and 209 Catholic. Other needs of the community were met by its 44 Public Houses. As the streets in which each family lived are named, it is instructive and heartening to see the mixture of different faiths on every street – a pattern arguably more integrated than in much of Ireland’s more recent past.

The library’s position – occupying the full length of the first floor of an imposing Georgian building; its relatively unaltered condition – apart from a sympathetic early extension it is essentially the building Robinson commissioned, and contains his collection still shelved much as it was in 1770; and its early status as a library – designed for serious academic contemplation and research as part of a serious development of Armagh’s city status at a time when Belfast, by contrast, was just a town – established constraints within which the installation would have to work. Nevertheless, the opportunity also arose to attract to the site visitors and residents who might not have considered visiting a historic library, and this too was understood to be an important objective for the project.

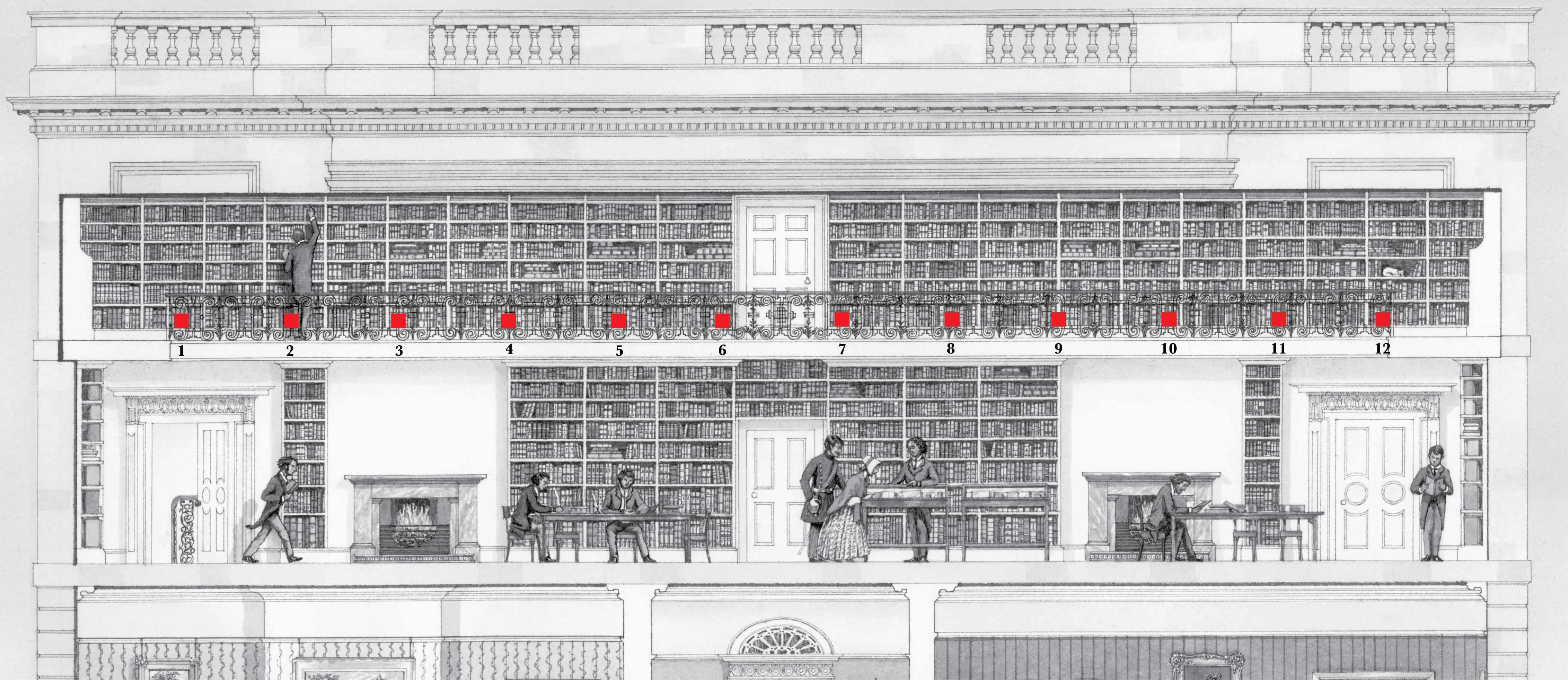

The scale and layout of the library, with its beautiful double-height windows, broken by a mezzanine balcony running around the entire room, immediately suggested another in a series of works in which a line (or lines) of small loudspeakers have been deployed, as in this context they might be inconspicuous but have maximal acoustic effect, affording clear spatial definition along the library’s length. The form of the piece was conceived around the recorded contributions of current Armagh residents, who were asked to read and respond to the lists of entries in the census. The data was presented in numerous tabular forms, organised by surname or by street name, and the interviewees asked to follow the various listed sequences:

“Acheson, John, labourer, 2 children, no servants, Lane off Irish Street;

Albeny, William, toll gatherer, no children, no servants, Big Meeting Street;

Allen, William, weaver, 3 children, no servants, School Lane….”

“Ardrea, Armstrong, Baily, Ball, Bambrick, Barnes, Bassett, Bell, Best, Bincks, Bingham…”

“Sextoness, shopkeeper, organist, sells liquor, britches maker, stonecutter, watchmaker…” etc.

The result was initially planned to be largely textural, a sound collage, with only occasional prominence given to a single voice. In the event the employment of one of my Masters students, Matt Irwin, to help with the recordings had a profound and unforeseen effect on the nature of much of the twenty hours of recorded material gathered. Matt’s local knowledge and ability to engage seemingly anyone in the community in conversation led to far more discursive, reflective material from the participants than initially anticipated, often delivered with disarming frankness or charm. This ‘storytelling’ aspect was encouraged, and the work began to take on an identity based on this added comment and vocal interaction/conversation, also drawing on the richly varied character of the voices. Different narrative strategies – some informational, some more performative – suggested clear ‘dramatic’ functions for the voices of several of the participants, who emerge variously as ‘narrator’, ‘chorus’ and ‘soloists’. The invisibility of the loudspeakers, and their position (on an inaccessible balcony) allows differentiated ‘layers’ to coexist within the room, and the placing of each voice in a particular location theatricalises the space with respect to the room’s considerable length, aiding a sort of positional legibility within which the audience can privilege their relationship with a particular character simply by moving nearer to the source of their voice. This continues a concern with the ‘navigability’ of installation works which was begun in my 2006 installation for the Sainsbury Centre of Visual Arts, Norwich: Proxemics: The World is a Deaf Machine.

The prosaic-seeming title of the current work is a quotation from Tobias Swinden’s 1727 tract ‘An Enquiry into the Nature and Place of Hell’, pages from an original copy of which have somehow found their way into the composer’s collection. As is frequently the case, the title was required long before the work was made, but in retrospect, the decision to position small speakers on the library’s pierced cast-iron balcony did indeed result in voices emanating from above.

The initial presentation of the work was reverential and performance-like, with a largely seated audience at the opening listening intently. Following this the work ran as an installation, often concurrently with other activities in the library. In this respect the ‘scaling’ of the work’s reproduced amplitude in the space proved crucial. The Anker loudspeakers chosen are neither powerful nor extended in range, but they are capable - with material of carefully-chosen frequency range - of good reproduction at reasonably low volumes. There is thus a contiguity between the ‘speech level’ reproduction of the installation, and the accretion of a further level of speech intervention by visitors to the library. Although libraries are quiet, here the installation animates the space, affording visitors the opportunity of speaking. My initial peevish ‘composerly’ response to this overlay of additional speech – that ‘people weren’t listening’ – was rapidly replaced by a realisation that the piece had genuinely met the conditions originally set out for it, assuming its own life. Just as vital material had emerged from the interviews ‘despite’ my initial intentions for it, the residents of Armagh were now completing the piece by absorbing it back into the community.

Audio

A stereo audio file (FLAC format) documenting the installation can be found here. This is a panned mix of the original sound files which distributes the voices approximately as they appeared in the installation.

Context and credits

The work was commissioned by Armagh City, Banbridge & Craigavon Borough Council and is dedicated to Carol Conlin of the Robinson Library, Armagh, whose enthusiasm was a key prerequisite of the project’s success. www.armaghrobinsonlibrary.co.uk

The spoken voices in the work are those of Thomas Ian Adair, Sean Barden, Stanley Burrows, Louise Chin, Stephen Hartley, Andrew Irwin, Matthew Irwin, George Lutton, Chloe Mahood, Gordon McDowell, Heather Stevenson and Ivor Stevenson and others. Technical support came from Matthew Irwin, whose local knowledge transformed the project, and from Miguel Ortiz and Craig Jackson at SARC (Queen’s University, Belfast).

Stephen Conlin’s illustration of the inside of the Robinson Library (here doctored to show the positions of loudspeakers) is copyright of and used by kind permission of Stephen Conlin. Stephen’s work can be seen at www.pictu.co.uk

Thomas Cooley’s original design for a window of the Robinson Library is reproduced by kind permission of the Governors and Guardians of Armagh Robinson Library.