Chapter Twelve - Mixing Sound

Dancing keys:

During a day of filming our “Waldstein” lecture, I was excited about one particular camera angle we had come up with. As a test for the camera operator, I played this bit from the second movement of Op. 54. I had always enjoyed that perfect groove where wrists and keys move in synchronicity. Turns out there’s visual pleasure too in seeing those wobbly keys respond to my hands’ rotations.

Mixing a French Beethoven:

Between February 11 and 15, 2019, in the Academiezaal in Sint-Truiden, Belgium, we recorded Beethoven and His French Piano: Sonatas Op. 53, Op. 54, and Op. 57 / Adam Sonata Op. 8 No. 2 / Steibelt Sonata Op. 64, a double-CD production released by Evil Penguin Records in 2020.

The recording dates should not fool us. It may be customary for classical music CDs to include those in the liner notes as a reference, but insiders know there’s an extended “post”-production process that includes another three stages of editing, mixing, and mastering. The activity of mixing became particularly revealing in the project on a piano that I had learned to appreciate for its fine sonority. This is the stage where one can focus solely on “the sound”—in this case also that “French sound” that we so diligently analyzed and that, as I argue in the book, also Beethoven tried hard to understand. That’s also why early on (and this decision ended up shaping the contents of the book as well) I decided to include in the recording project works by Louis Adam and Daniel Steibelt. They spent entire careers developing their craft on French pianos, after all, so whatever sound they created on these instruments would be a very useful benchmark—for me, but hypothetically also for Beethoven.

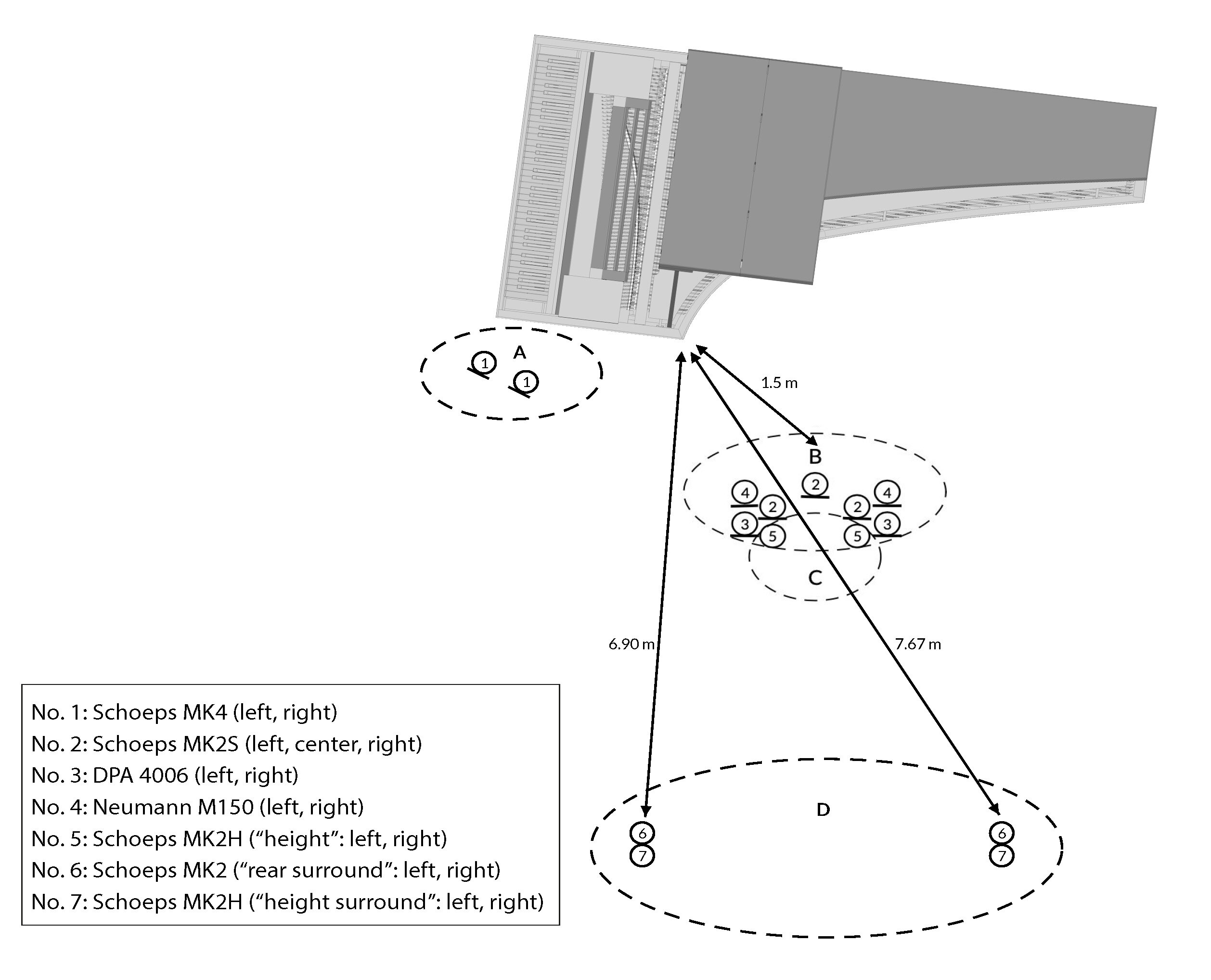

The figure below shows a diagram of the various microphones we used, numbered from 1 to 7. They come in pairs (left, right), and no. 2 comes as a trio: left, center, and right. Dotted circles show layers of sound, from A to D, corresponding to the various areas where microphones were positioned, from close to the instrument to further away in the room: photographs help visualize this set-up.

The idea behind using an array of microphones is to create options for the mixing of recorded sound. Not only does each microphone come with its own built-in characteristics, which may be combined with others, but they’re also placed at key listening positions across the room, allowing the mixing engineer to construct a listening perspective that combines also the best qualities of the room.

Here’s my main argument in regard with Beethoven’s wannabe trilogy of sonatas, Op. 53, Op. 54, and Op. 57. Through these sonatas, written and published between November 1803 and February 1807, Beethoven explored the affordances of his French piano. But these explorations were seriously hindered, if not rendered impossible, as the instrument underwent revisions—even if these very frustrations started informing the creative process (and thus, in some twisted way, became essential and necessary) of Op. 57 and the publication of Op. 53.

My replica was (and still is) unrevised—making it perfect for Op. 53 (especially its pre-published version) and for Op. 54, but problematic for Op. 57. The latter I realized when the piano was rejuvenated, that is, its leather hammer coverings refreshed, just two weeks before those special recording dates. While I felt confirmed in my uncut, bouncy, and jubilant “piano e.f.d. clavecin” version of Op. 53 (spared of the objections that Beethoven had to deal with when preparing his “Waldstein” for publication), I started having serious doubts about Op. 57: was I going to be able to capture the fraught interaction of instrument and player that this piece demands? Was I going to be able to put the “y” in Beethoven’s dependence on his Erard? Was the instrument suddenly not too pristine?

Microphones, however, would help me out, or so I told myself. Well, did they?

During postproduction, we indeed ended up changing our mix as we moved from Beethoven’s Op. 53 and Op. 54 to Op. 57, but also mixed Beethoven differently to Adam and Steibelt. To be sure, these differences are slight (a generic “French sound” still unites the three pianist-composers), but the fact that these small adjustments were implemented across two very clear lines—differentiating within Beethoven (to reflect a shift from dependence to dependency in regard to his own instrument) and between Beethoven and his French counterparts (to reflect foreignness vs. fluidity of tone or style)—raises intriguing questions, indeed.

Important to emphasize too—which makes the results even more striking—is that these decisions involved a whole team, including the two sound recording engineers Ephraim Hahn and Kseniya Kawko (then McGill University graduate students) and Tonmeister Martha de Francisco, who directed the overall recording project.

On December 22, 2021, long after our mixing sessions in May and June 2019, Martha and I met up again at the Critical Listening Room of CIRMMT in Montreal, Canada. Keen to both confirm and rationalize what our ears had so unanimously told us, we opened our files once again and submitted our past decisions to systematic re-evaluation. We selected three key fragments: the first minute and a half of Steibelt’s Op. 64, Beethoven’s Op. 53, and Beethoven’s Op. 57.

The three slide shows below, one for each recorded fragment, reproduce this listening session. I invite you to listen to each pair of microphones separately, preferably using a good set of headphones: first from no. 1 to no. 4, then from no. 5 to no. 7. After no. 4, you will be ready to assess our mix of layers A and B (amounting to the "close sound" of the instrument) and after no. 7 to appreciate the full mix of layers A-D (this "complete sound" now also including room).

I also offer my own, subjective commentary, edited from my notes during our listening session.

Fragment 1. Steibelt, Sonata Op. 64, first movement, mm. 1–20:

Fragment 2. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 53, first movement, mm. 1–43:

Fragment 3. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 57, first movement, mm. 1–20:

What have we been mixing?

In the book I suggest that the recording allows us, rather than listening to a Beethoven sonata, to hear, through that sonata, Beethoven listen to his French piano. Broaden the definition of “listening to” to “interacting with,” and the three elements of composition (those sonatas), instrument (the French replica), and pianist (Beethoven, Adam, or Steibelt—by proxy, I) become agents in a complex yet intensely visceral activity that extends from the piano bench to the mixing room.

“Go sit at the back of the room, close your eyes, and listen,” Steibelt is reported to have said to Charles Chaulieu, a student in the class of Adam, before playing the Adagio from his Grand Sonata Op. 64 (emphasis added). Steibelt’s focus on sound was remarkable. Undoubtedly, he would have demanded the same level of attention of a present-day sound recording engineer.